Since the ritual of Female Genital Cutting (FGC) involves the clitoris, it seems important to learn more about this organ and its function. But first a bit of history, or—more appropriately—herstory.

In over 5 million years of human evolution, only one organ exists for the sole purpose of providing pleasure — the clitoris. Yet, from ancient times to the present, the anatomy of the clitoris has been discovered, repressed, and rediscovered. Hippocrates, the Greek physician, born circa 460 B.C., called the clitoris “columella”: the little pillar. About 500 years later, Galen, an anatomist renowned in Rome, denied its existence. Centuries later, the 1901 edition of Gray’s Anatomy included a drawing of the female pelvis in cross-section, showing a small protrusion with the label “clitoris” (Gray, 1901). In the 1948 edition of Gray’s Anatomy, there is an analogous illustration of female genital anatomy (Goss, 1948). Yet, the label of the clitoris is now gone. The clitoral protrusion of the older illustration is also removed. As a result, the clitoris has now been erased (Moore & Clarke, 1995).

Just The Tip of The Clitoris

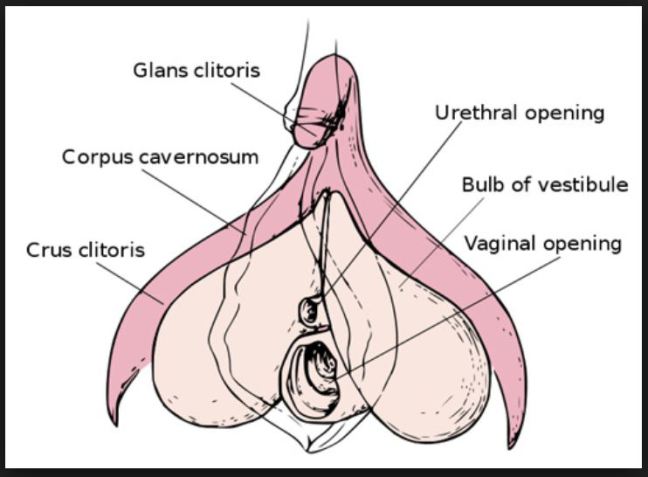

In reality, what we generally think of as the clitoris—what we can see and feel—is just the pea size tip of the clitoris, called the “glans”. The glans, located at the top of a woman’s vulva, at the point where the labia majora meet (near the pubic bone), contains approximately 8000 sensory nerve fibers—more than anywhere else in the human body. In fact, the amount of sensory nerve fibers in the glans is twice the amount found on the head of a penis.

More Than Meets The Eye

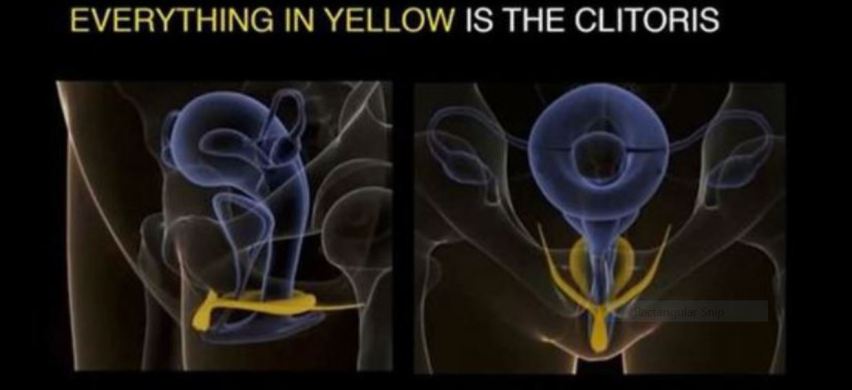

Many people assume that all there is to the clitoris is the glans, but with the clitoris, what you see is not what you get. Helen O’Connell, an Australian urologist, and her colleagues have corrected that misconception (O’Connell, Sanjeevan, and Hutson, 2005). Using modern imaging techniques such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), O’Connell has shown that there is much more to the clitoris than what meets the eye. They discovered that the glans of the clitoris is simply the tip of an extensive organ.

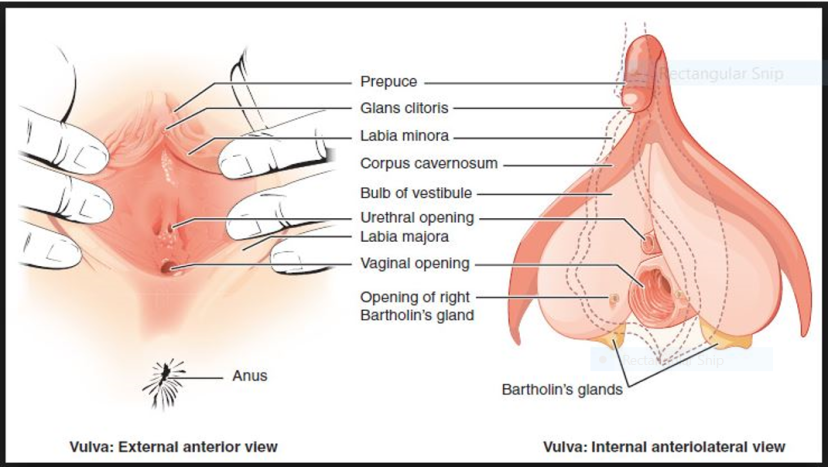

In fact, three-quarters of the clitoris is inside the body. As shown below, the clitoris is a wishbone-shaped structure that is about 3 ½ in. (9 cm) in length and 2 ½ in. (6 cm) in width. The glans extends backward into the clitoral body. The glans then split into the two leg-like parts, the crura, which are composed of erectile tissue and are next to the vagina and urethra (see MRI photo below of internal clitoris). The vestibular bulbs are two elongated masses of erectile tissue situated on either side of the vaginal opening.

The Clitoris and Its Place within the Vulva

The vulva is a single term used to describe all the external female genital organs. These organs include the labia majora, the labia minora, the clitoris, the vestibule of the vagina, the bulb of the vestibule, and the glands of Bartholin. The two sets of labia (lips) form an oval shape around the vagina. The labia minora are smaller and surround the vagina. The labia majora are larger, and, after puberty, the outer part of the labia majora is covered with pubic hair.

Since there are large portions of the clitoris extending through the pubic area, sexual responsiveness is not limited to direct or indirect stimulation of the clitoral glans (Wallen and Lloyd, 2011). Due to this extended internal structure, the clitoris can respond to stimulation of the external vaginal labia, the vagina itself, and the anus. As a woman draws closer to orgasm, the clitoris can swell by 50 percent to 300 percent. According to O’Connell, “The vaginal wall is, in fact, the clitoris.” If you lift the skin of the side walls of the vagina you will find the bulbs of the clitoris (O’Connell 2008). O’Connell proposed the notion that during vaginal intercourse it is the “clitoral complex” that is stimulated.

Clitoral anatomy and FGC: Removing the glans of the clitoris does not mean the whole organ is destroyed.

The issue of clitoral anatomy is also significant concerning the practice of clitorectomy. Type 1 FGC: Often referred to as clitoridectomy, is the partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals), and in some cases, only the prepuce or hood (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris). The clitoral hood varies in size, shape, thickness, and other aspects of its appearance from woman to woman. Some women have large clitoral hoods which appear to cover the clitoral glans. Others have much smaller hoods which leave the clitoral glans exposed. While the biological function of the clitoral hood is simply to protect the clitoral glans from friction and other external forces, this body part is also an erogenous zone. It provides natural lubrication, which makes stimulation of the clitoral area more pleasurable. As the clitoral glans itself is often too sensitive to touch, many women gain pleasure from having the glans indirectly stimulated through the clitoral hood.

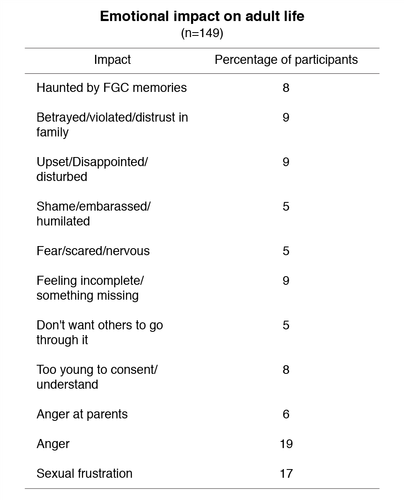

Although female sexual pleasure is often hindered by clitoridectomy, many women report that they are still able to enjoy sex (Lightfoot-Klein, 1989, Kelly and Hillard, 2005). One researcher has found that even infibulated women may still have the ability to achieve orgasm. Dr. Lucrezia Catania, who has studied and treated FGC-affected women in Italy for two decades, has found that when some of the sensitive tissue of the labia minora and clitoris remain intact, infibulated women can experience orgasm, while others cannot and instead feel pain.

Pelvic Nerve

The clitoris has enormous potential for arousal, but what may affect sensitivity is the supply of nerve endings and the individual pattern of each clitoris, which explains the variation in women’s preference for stimulation. The pelvic nerve branches in individual ways for every woman. The pathway distribution is quite different and far more diffuse from male sexual wiring, which is much more uniform.

Some women’s nerves branch more in the vagina while other women’s branch more in the clitoris, or in the perineum (the skin between the anus and vagina) or in the mouth of the cervix. No two women—not even identical twins—have the same pattern and distribution of nerves. This complex system of nerve endings extends into the pelvis and is in fact far larger on the inside than it is on the outside. When stimulated, the erect clitoris tightens around the vagina. This means that “vaginal orgasms” are actually caused by the clitoris, not nerves on the vaginal walls themselves. Whether brought on by penetration or external stimulation, all orgasms are clitoral.

Not only can the anatomical facts of the clitoris help alter cultural biases and mythologies, but correct knowledge of clitoral anatomy may help enhance a woman’s appreciation and experience of her body.

The information for this article was sourced from:

Blechner, Mark, J., “The Clitoris: Anatomical and Psychological Issues.” Studies in Gender and Sexuality, 18:3 (2017): 190-200.

Wolf, Naomi. Vagina A new Biography. New York: Harper Collins, 2012

The images included were researched from internet sources.

This is part five of a seven part series. Check back for Trauma and Female Genital Cutting, Part 6.